Talking Heads made waves in the 1970s and ’80s with their unique new wave and post-punk sound, and in 1980, they pulled from a unique variety of influences to compose what is often considered their magnum opus: Remain In Light.

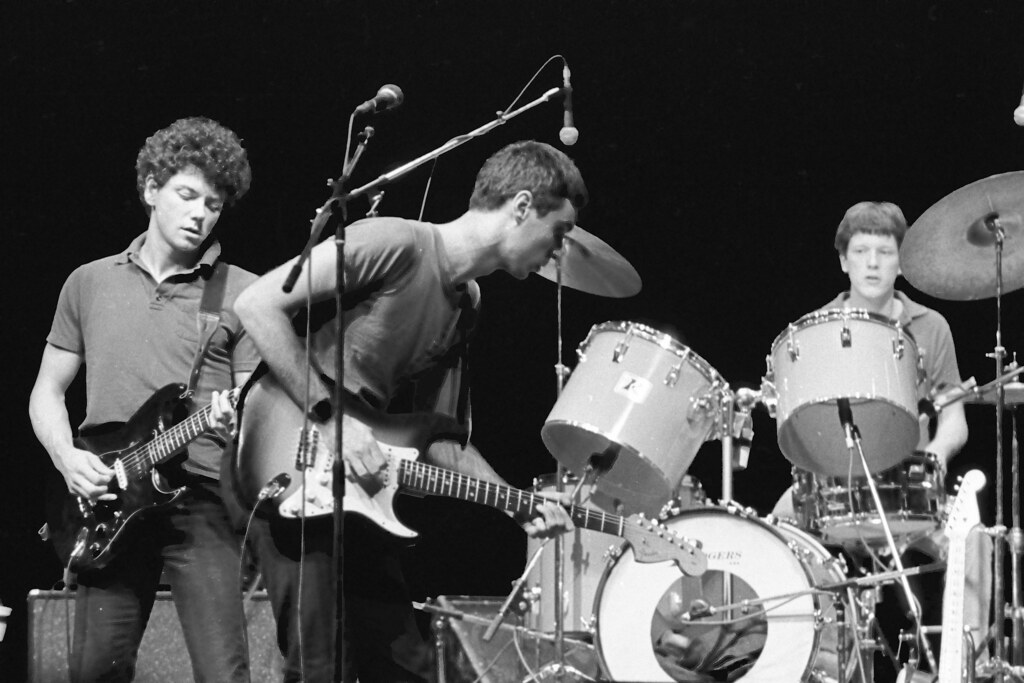

Background: The original trio of what would become Talking Heads was formed in the mid 1970s through the companionship of three students at the Rhode Island School of Design. The group began as composed of David Byrne on vocals and guitar and Chris Frantz on drums, with Chris later adding his girlfriend Tina Weymouth on bass. They named themselves The Artistics, though they would soon break up and move to New York. Jerry Harrison would join the band on keyboard after they moved, and they would perform at various gigs in New York, including the popular New York music club CBGBs. There, they would open for The Ramones in 1975, the same year they officially declared themselves “Talking Heads.” Their performing eventually got them noticed by record labels, and they would sign to Sire Records, through which they released their first three albums (Talking Heads: 77, More Songs About Buildings and Food, and Fear of Music) during the latter half of the 1970s decade. The band’s sound consisted of a unique blend of new wave, art rock, punk, post-punk, and dance music, and though they had not yet reached their commercial breakthrough, songs such as “Psycho Killer.” their cover of Al Green’s “Take Me to the River,” and “Life During Wartime” would become some of the band’s more well known songs. Their fourth album, and their introduction to the ’80s, would involve inspiration from a variety of new influences: Remain In Light.

After the release of Talking Heads: 77, Byrne would meet with experimental rock artist and producer Brian Eno (who worked on David Bowie’s Low, one of my favorite albums of all time, please check out my article on that!), and the band would begin to work with Eno. He would produce the band’s second, third, and fourth albums, which naturally included Remain In Light. Around the time period between the releases of Fear of Music and Remain In Light, Talking Heads was busy trying to prove their worth as a unit, as Byrne’s more controlling attitude towards the band was fairly well known. The band began to work more closely together, and the introduction of Afrobeat musician Fela Kuti to the band by Eno, as well as Chris and Tina’s extended stay in the Bahamas where they were influenced by reggae and Afrobeat musicians, would help lead to Remain in Light‘s sound leaning more towards African music and polyrhythms, which came with a sense of “communal playing.” Even influences from the then young hip-hop genre would bleed into the band’s creation process, such as its constant use of looping, or sampling, to continuously play the same musical sections while artists rapped over them. On October 8, 1980, Remain In Light, was finally released.

Production/Instrumentals: Produced primarily by Eno, the sound of Remain In Light is funky yet ominous, as though many of the songs on this album have prominent grooves and an emphasis on catchy rhythms, the robotic and inhuman sound of the album creates an odd combination that works surprisingly well. The repeating bass twangs of opener “Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On),” for example, can easily worm their way in one’s head, and yet the descending notes in the background and the song’s unnerving tone bring a sense of looming danger all the same. The quicker guitar notes on “Crosseyed and Painless” and the horns, dissonant guitar solos, and repeating group chants in “The Great Curve” carry out this unorthodox style of funk as well, and Byrne’s dramatic delivery on the choruses of both and the continued layering of vocals on the latter further that sense of unease. The warm and colorful synth notes which repeat throughout the hit song “Once In A Lifetime” give off a similarly catchy but eerie feeling, especially when paired with Byrne’s more shocked delivery. The first four tracks of the album are more overtly funky and are almost cartoonish in their exaggerated grooves.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Meanwhile, the second half of the album is much more relaxed by comparison, though ear-catching in its own way. As the record approaches a slower pace, the album’s more ominous tone becomes that much more prominent. Musical moments such as the sparse bass notes and Byrne’s more casual delivery on “Seen and Not Seen” and the haunting atmosphere presented on closer “The Overlord” see the album take a more minimal approach that admittedly helps to diversify the tone of the album. The album’s musical influences can also be seen within the band’s instrumentals as well, such as the afrobeat inspired drum loops of “The Great Curve,” “Once In A Lifetime,” and “Morning Wind,” the growing communal chants in “The Great Curve” and “Houses In Motion,” the hip-hop inspired drums of “Seen and Not Seen,” and the overt funk influence in its grooves altogether. The overall execution of the album’s instrumentation was unique for the album’s time as well. Hip-hop helped inspire the fact that all of the album’s songs are made of continuous, looped grooves or instrumentals, and though they still change and vary at certain moments, they keep a consistent, repetitive rhythm going throughout each song. These loops can have a hypnotizing effect on the listener, bringing them further and further into the world of each song.

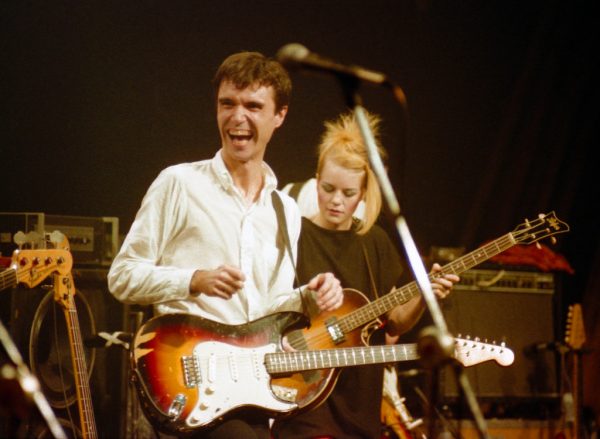

The performances from the rest of the band, particularly Byrne, really help to accentuate the album’s sinister feeling. Byrne himself sings in a fairly disorganized fashion, nearly yelling out certain lines and questions on “Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On)” and “Once In A Lifetime,” and leading a growing chant of sung lyrics on “The Great Curve” and “Houses In Motion.” He often follows a pattern of shouting or yelling out his verses, but singing in an off-kilter fashion during the drawn out choruses, both of which come off as investing. His unique voice is used to great effect on this album, and so are the performances from the rest of the band members. Weymouth’s exaggerated and versatile bass-lines (both in tempo and style) contribute immensely to the album’s catchiness, as do Harrison’s equally invigorating guitar notes and Frantz’s drum loops, which like the bass-lines, do become more relaxed in the second half, but still contribute to the record’s sound in a very essential way. Every member of the band plays into the album’s themes while being unafraid to sound odd in the process, which results in an album that stands out and makes itself sound confidently unique.

Songwriting: Throughout Remain In Light, Byrne employs an abstract writing style, often delivering lines unpredictably and abruptly, as if they are being thought of in the moment. A lot of the lines in the album can feel disconnected from each other, and can appear unexpectedly, though they do come to form some sort of message. For example, many of the songs on Remain In Light deal with the restricting confines of living a conventional life, and the limits of being what is considered human (though the album’s lyrics are very much up to interpretation; these are just my own thoughts.) Whether it be Byrne’s dismissive nature towards facts and their restrictive nature on his rap-inspired verse on “Crosseyed and Painless” or Byrne claiming that he is “walking a line. Just barely enough to be living” on “Houses In Motion,” the group displays a resentful attitude towards the confines of modern society, and a willingness to break free of the expectations placed on them. The group also looks at the way life can bring its set of struggles in “Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On)” and how it can lead one to places they feel trapped in and uncomfortable with in “Once In A Lifetime.” The struggles of remaining what is often considered “human” and “respectable” are a common, if not the most common, theme throughout the album, though they may be executed in different ways. One form of execution is storytelling, as the lyrics of “Seen and Not Seen” and “Morning Wind” both tell their own stories, the former about a man trying to alter his facial structure to fit in with others, and the latter about a native named Mojique who rises against the American people, though the latter has a more ambiguous interpretation. Overall, the album’s songwriting style, like many other aspects of the album, is unorthodox yet effective, bringing a unique twist and abstract style that makes the album’s lyrics that much more exciting and intriguing to interpret.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Personal Enjoyment: Personally, I find the first half of this album to be constantly exhilarating and exciting, even on repeat listens. I think the amount of energy brought by the band members and the zany instrumental loops contribute a lot of character and creativity, particularly on “The Great Curve,” which has grown to become one of my favorite songs in recent memory. The looping instrumentals grow even catchier as they continue on, and Byrne’s sung and yelled vocals, as well as the rest of the band’s exaggerated performances, immerse me further into the album’s sound with each song. I especially enjoy Byrne’s sung choruses, as they bring an ominous edge that is nonetheless intriguing and contains a sense of hypnotism not as present in his verses. However, though I do praise the band for not being afraid to change their sound and being able to experiment further, I find the second half to be more underwhelming by comparison.

David Byrne & Tina Weymouth” uploaded to Flickr by Craig Howell

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

I enjoy the more relaxed grooves on “Seen and Not Seen” (which has grown on me quite a bit during the re-listen for this article) and “Houses In Motion,” but the drawn-out and more minimal guitar-led closer “The Overlord” and the slow pace of “Morning Wind” did not leave as much of an impact, in stark contrast to earlier songs such as “The Great Curve” or “Crosseyed and Painless,” which grew more and more exciting by the minute. Essentially, as the album diverted further from the funkier first half, I began to feel more underwhelmed personally. However, I do think that the run of songs from the opener to the third to last song, “Seen and Not Seen,” is still more than worthy of praise as an incredible string of songs. The album’s more vague and sporadic writing style altogether does a great job of conveying its themes of humanity, using a unique writing style and delivery to explore the importance of being a unique person and leading a unique life. The band brings a lot of personality in everything they do with this album, something which I feel a need to appreciate. Though it may not be one of my personal favorite albums, it still deserves recognition as a landmark new wave album of the ’80s. I find this album intriguing because it tells the story of a band taking their own set of influences, ones not commonly explored in the U.S. at the time, and translating them into a product that only they could make. There is a lot to appreciate about Remain In Light in that regard, as well as many others, and it is for this reason that I wrote this article. Now, feel free to go check out Remain In Light on your own and form your own opinion, especially if you disagree about the latter half.

Further Sources on Talking Heads and Remain In Light:

https://k-zap.org/music_profiles/talking-heads/

https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/the-story-of-talking-heads/

https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/the-music-that-inspired-talking-heads-album-seminal-remain-in-light/

https://happymag.tv/talking-heads-remain-in-light-why-it-mattered/