Meet the MHS Valedictorian Who Died in WWII

A Proud Patriot from the Class of 1935

Vincent Russell Brown, MHS valedictorian whose name is now enshrined on the Wall of Freedom

May 19, 2022

Meet Vincent Russell Brown, the valedictorian of Mentor High School’s Class of 1935. Known as “Russell” by his family and friends, Brown was born on November 19, 1917 in Green County. He grew up in a house on Route 20 with two younger sisters, Elaine and Carolyn, and attended Mentor High School. Being deemed “valedictorian” is no easy accomplishment, yet Brown claimed this honor with pride as he approached his high school graduation.

But if we take a step back, we will remember that life was not the greatest in the 1930’s. The people of the time were suffering from the Great Depression, and they were hearing stories of what was happening in Europe. While President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was trying to heal the country from economic hardships, Hitler was invading Poland and initiating World War II. One could only imagine what Americans were reading in the newspapers as the war began to develop.

Brown completed his first year of college before he decided to enlist in the United States Selective Service. He was inducted into the U. S. Army on March 1, 1941, in Cleveland, months before the Pearl Harbor attack. His initial post was at Ohio Rubber Company, where he was assigned to C Company, 192nd Tank Company. Eventually, Brown was transferred to Fort Knox, Kentucky, were he completed basic training. This training consisted of infantry drilling, music marching, machine gun training, pistol training, rifle firing, getting equipped to gas masks and gas attacks, pitching tents, hiking, as well as gaining in-depth knowledge on the weapons in which he would be using, such as assembly and cleaning. According to Bataan Project, this is where he earned the nickname “Brownie.”

Brown’s assignment placed him in one of the first armored units and eventually took him over to the Philippines. Unfortunately, as Thomas Matowitz says in his article, his placement in the Philippines was a “tragic irony.” At the time, World War II was only in Europe and no one considered that there would be any other fronts, so it seemed as though Brown was in a relatively safe position. But shortly after Brown’s arrival to the country, the Japanese attacked and he was taken as a prisoner of war.

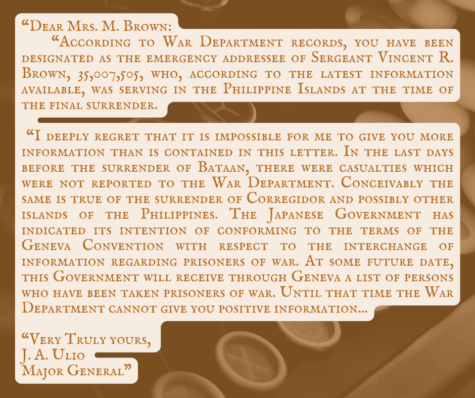

His parents received this letter in May/June of 1942 from the War Department, reading:

For three years, Brown survived the brutal treatment of the Japanese camps, were the death rates were 50 men per day. The men were put in barracks that were meant for 50 people, yet 60 to 120 POWs were placed in them. The POWs endured long and difficult hours of labor chopping endless amounts of wood, working vigorously in fields, building runways without machinery, and burying their dead comrades in mass graves. The punishments were cruel and sickening, yet Brown never gave up.

Worst yet, the American government couldn’t even confirm Brown’s status to his family to state whether he was alive, injured, or dead. In July of 1942, his parents received an apology letter saying that the United States was unable to determine whether their son was alive or not. The Japanese were not cooperative in giving lists of the deceased and POWs, so many families didn’t know whether their brothers and sons would ever make it home. The Brown family lived in a constant state of uncertainty for years before they got another letter from the Army.

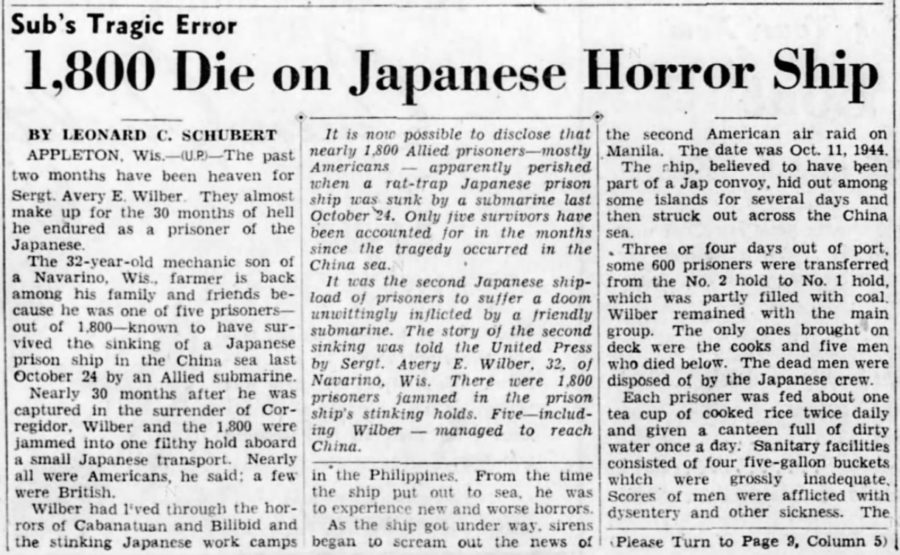

In fact, the Army became aware of his death once they found out that a Japanese submarine filled with American POWs was torpedoed. The Japanese forced over 1800 POWs into the ship Arisan Maru to be transported back to Japan and the living conditions were absolutely appalling. Calvin Graef, a survivor, said, “There were so many (that died) out of 1800. The conditions in the hold…..men were just dying in a continuous stream. Men, holding their bellies in interlocked arms, stood up, screamed and died. You were being starved, men were dying at such a pace we had to pile them up. It was like you were choking to death. Burial consisted of two men throwing another overboard.” The experience was horrific and sickening, yet these men faced this treatment on the Arisan Maru for an unknown amount of time until they heard sirens.

On October 24, 1944, bells and sirens were ringing, warning the ship that submarines were

approaching. American submarines were on their way to the Japanese ship, ready to attack. It is imperative to realize that the Americans were intercepting Japanese communications at this point in the war. To counter the breach in communication, the Arisan Maru crew-mates carrying the POWs were not aware that they were transporting POWs until last minute notice, so the American submarines did not know that they would be firing upon American men.

So as the sirens rang throughout the Arisan Maru, the POWs devastatingly cheered, hoping that a rescue was underway. But when they felt the first torpedo hit the submarine, they grew defeated, but were also relieved, knowing that the torture they’d endured was going to be over and death would end their pain. When Lt. Robert S. Overbeck was asked about this day, he said, “When the torpedoing happened, most of the Americans didn’t care a bit–they were tired and weak and sick.”

After getting hit by two torpedos, the Arisan Maru, which was carrying 1,775 men, sank and only nine POWs survived, eight surviving the war.

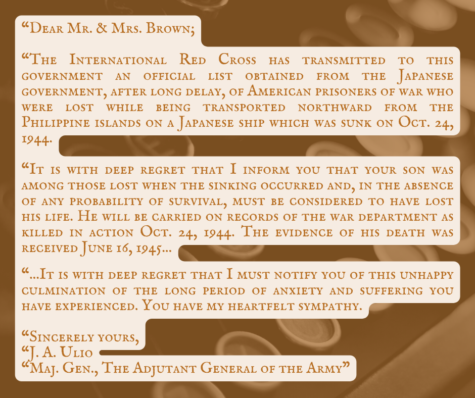

After years of not knowing about their son, Brown’s parents received their final letter from the Army:

Vincent Russell Brown enlisted to protect American lives and tragically suffered for three years under Japanese imprisonment before passing away. For three whole years he was brutally tortured and endured forced labor overseas. It is difficult to picture a young man strolling the halls of Mentor High, which is now Memorial Middle School, and realizing that he is the same war-torn soul who was killed in World War II. The boy who was cherished by his community and successful in his education was taken away from the earth too quickly and suffered in a way no person should.

Brown remains on Mentor High’s Wall of Freedom and his name is spoken annually at the Veteran’s Day assembly. Let us never forget that this man, the valedictorian who accomplished so much here at MHS, sacrificed his life for our country and lived through more pain than we could ever imagine for our freedom.

If you are looking for more information regarding Vincent Russell Brown and his journey, check out the Bataan Project, for they have an immeasurable amount of detailed information regarding his military life.